Though not a creature one typically meets in the wild, I’ve had two impactful encounters with bats.

The first happened one night when I was awakened by an unusual swishing sound above my bed. A bat was circling overhead! I grabbed my dog and ran out of the house in the middle of the night. Never did find the bat but I have since learned the best thing to do in that situation is open the windows and doors, remove any screens, and turn on a porch light to attract the bat towards flying insects. Plus, I need not have feared since out of the 1 billion bats worldwide only 1% have rabies.

My second meeting with bats took me to the scenic Ozarks in Arkansas. On a hike, I followed a group of teens into a cave I didn’t even realize was there. Crawling and squeezing through tiny passageways, we emerged into a breathtaking cavern, where we saw a voluminous four-story waterfall coming from the Buffalo National River. After being awestruck by this sight, I noticed out of the corner of my eye that the black ceiling seemed to be moving. If you guessed the ceiling was filled with thousands of bats, you would be right!

Diversity and Challenges

Further research has revealed a disheartening update: the cave I ventured into has been closed since 2009 due to a highly transferable fungus called white-nose syndrome (WNS) that spreads among bats, transferred from clothing and shoes. This affliction, first discovered in New York in 2006 and later spreading to Pennsylvania in 2008, develops while bats are hibernating and attacks their ears, noses, and wings. The fungus disrupts their sleep, causing increased movement which depletes their energy reserves. Sadly, this leads to the death of most bats affected.

The impact is devastating: over 90% of little brown bats and Northern Long-eared bats have succumbed to white-nose syndrome across Pennsylvania.

The U.S. and Canada are home to about 45 species of bats, adding to the over 1,400 species worldwide. Pennsylvania has 9 species of bats with two species on the Federal Endangered Species List (Northern Long -eared bat and the Indiana bat) and 2 bat species on the state Endangered and Threatened Species list (tricolored and little brown bat).

The little brown bat, devastated by white-nose syndrome.

Peculiarities and Longevity

Did you know that each night, bats can eat their body weight in insects, numbering in the thousands! Due to their fast metabolism a bat can eat its body weight of insects in 30 minutes. This insect heavy diet not only helps foresters and farmers protect their crops, it allows those of us who enjoy gazing at the stars and listening to night sounds do so without being eaten alive by mosquitoes!

The difference in the size and weight of bat species is both significant and impressive. They range in size from the Kitti’s hog-nosed bat (known as the Bumblebee Bat) that weighs less than a penny — making it the world’s smallest mammal — to the flying fox bats, which can have a wingspan of up to 6 feet.

The flying fox and the Kitti's hog-nosed bat.

Bats exhibit interesting characteristics, from flying speeds of up to 100 miles per hour to their varying lifespans. While most wild bats live less than two decades, there are exceptions, with a Siberian bat setting a remarkable world record of 41 years!

When it comes to the young ones, babies are called pups, and are fed breastmilk (remember, bats are mammals!) before transitioning to a diet of insects. Most bats give birth to one pup annually, except for one species which births twins. Mother bats form nursery colonies in spring, often within caves, dead trees, or rock crevices.

Bats are also healers and informants for science. Remarkably, about 80 medicines come from plants that rely on bats for survival. Additionally, scientists have studied bats’ use of echolocation to develop navigational aids for the blind.

This hoary bat is a patient at Pennsylvania Bat Rescue.

Conservation and Action

According to Steph Stronsick at Pennsylvania Bat Rescue, if you find an injured bat wear gloves and place the animal in a container with a secured lid. Do not place it in a tree. The fact of finding a bat indicates injury and/or dehydration. Contact Pennsylvania Bat Rescue, who have rehabilitation expertise along with the adequate resources necessary for an injured bat’s survival. They rehabilitate approximately 300 bats per year.

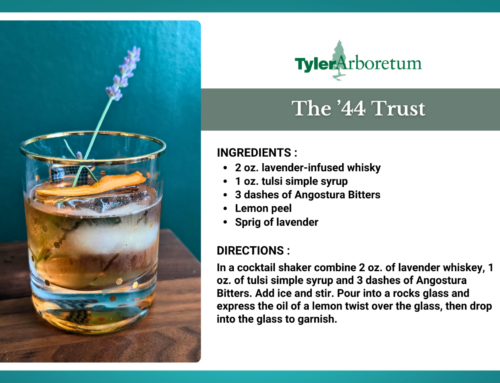

You can help this keystone species, on whom much of our environment and landscape depends, by learning more about bats at Tyler Arboretum on August 23, 7:00-8:15 PM for “Nature at Night: The Mysterious World of Bats!” (registration required) or by planting a bat garden, installing a bat house, avoiding harmful pesticides, and staying out of closed caves.

Bats have been around for 52 million years, let’s unite to safeguard these unique creatures, ensuring they are around for another 52 million years. They need us, just as we need them – can you be counted on to help?

Found a bat? Have a question? Want to volunteer, attend an event or learn more? Check out PA Bat Rescue for all your bat related needs!