After the past few weeks, I think we’ve all got rain on the brain. Following a few days of misty, soggy weather, everything can start to feel saturated. While it’s nice not to need to worry about watering our vegetable gardens or new plantings, all this rain leaves us with a question.

Did it use to rain this much?

The short answer is – no, it didn’t. Overall, due to climate change, Philadelphia is facing warmer, wetter summers. The Philadelphia Water Department reports that since 2004 we’ve seen a significant increase in both frequency and severity of storm events, which has led to severe flooding throughout the city (Useful Climate Information for Philadelphia: Past and Future, August 2014).

That isn’t good news for our area, especially when you consider that our neighborhoods, towns and cities have always coped with stormwater (the water that falls during storms) by funneling it away from our properties into a system of tunnels below ground, called the stormwater system. That means rain that hits our roofs, driveways, streets and sidewalks runs off quickly and is directed into those pipes, along with all the dust, bits of litter, oil spots and other residues that it picks up along the way.

The problem in the Philadelphia area is about 60% of the water collected goes into our Combined Sewer Outfall, which essentially means stormwater mixes with water from our sewer systems. That sounds like a good idea. That way all the water can be treated and the pollutants removed, right? Maybe. But with more and more rain – and aging pipes – often the system overflows and expels the untreated sewer water and stormwater directly into our rivers and streams. The other 40% of our area is served by a Municipal separate stormwater system, which doesn’t attempt to treat the collected rainwater at all. In this system, stormwater and all the pollutants it carries with it are directed into the nearest waterway. All together that’s bad news for everyone, from the wildlife that relies on those waterways for survival, to the people who use water from the Delaware River for their drinking water.

The aging system, combined with increasing human population and more projected rainfall, means that the greater Philadelphia area is facing a serious stormwater problem. The problem comes with a serious price tag as well. According to the paper ‘Financing Stormwater Retrofits in Philadelphia and Beyond’, the EPA projects that repairing the nation’s aging stormwater system could cost up to 100 billion dollars nationwide over the next 20 years.

That’s a lot of money, and ultimately every person in America would be involved in paying for it, whether through taxes, fees or repairs on their personal property.

What if there was a better way? What if we chose to rethink the way we address stormwater management as a whole, instead of just looking at the cost to repair and replace pipes beneath the city? What if we took a step back and tried to solve this problem, not just for right now, but for the future?

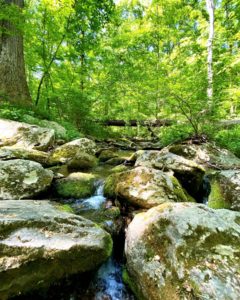

The good news is that we don’t need to look far for the solution. Imagine rain falling on a forest or meadow. The trees, grasses, flowers and other plants slow the force of the water so that it hits the soil more gently. You can see this yourself if you stand beneath a tree during a storm, the water drips slowly down, continuing to fall even after the rain stops. From there the water soaks into the soil – rather than running off of concrete. The roots of the plants take it up and return it to the atmosphere. The pockets of air in the soil, as well as the plant roots, fungal hyphae, macro and micro invertebrates and the entire soil community help trap pollutants. The water recharges the groundwater system, which feeds our streams and rivers as they flow toward the Delaware Bay and the ocean beyond. That is the cycle without human interruption. We disrupt that cycle when we remove the natural community and place impervious surfaces (or surfaces that cannot absorb water) over the soil.

The stormwater issues we face in Philadelphia, and beyond, are problems for the whole community. Increased flooding will damage homes and neighborhoods, often in areas where people are living at or below the poverty line. Poor water quality will harm the vast interconnected web of ecology that gives this part of Pennsylvania its sense of place. Every member of our community, from humans to wildlife, will suffer if we don’t take action.

Community problems call for community solutions. The price tag for repairing our stormwater system in the Philadelphia area is high, but there is a great deal that we can do as citizens to help restore the natural water cycle. And every time you do that the cost of clean water goes down, and the quality of our local streams, rivers and drinking water goes up.

So what can you do? Here are just a few strategies that can make a real impact on your community.

Install a Rain Barrel

This is by far one of the least expensive and lowest maintenance options. Rain barrels connect directly to your gutter’s downspout and capture the rainwater that falls on your roof when it rains! That water is stored in the barrel until you need it. Most rain barrels come with a spigot that you can attach a hose to, or fill a watering can from, so that you can use the stored rainwater in your garden when the weather is hot and dry. This keeps that water from ever entering the stormwater system – and takes care of your garden at the same time!

This one takes a little more effort, but it’s a good one to keep in mind. If you need to replace your existing driveway, repair your sidewalk or install a patio, consider using permeable pavement. Even if you don’t cover the entire area with permeable pavement, a few strips along the sides of the project will give rainwater a place to soak down into the soil before it gets to the storm drain. Permeable pavement looks very similar to traditional pavements. Care is a little different – you don’t want to put sand down to address slippery surfaces and it’s a good idea to periodically pressure wash it to make sure it doesn’t get clogged. But overall the input is minimal and the benefits to your community are big.

Plant A Rain Garden

This one might be my favorite solution of all. A rain garden is a space that naturally collects runoff, whether because it sits in a low-lying part of your property, or because you dig a depression that you direct water into. Funneling water into a rain garden, rather than a storm drain, allows you to capture the water on your property, direct it to a space where it won’t cause damage or flooding, and have it soak slowly into the soil where it can re-enter the groundwater system. It’s the natural cycle of a forest or meadow – shrunk down to a smaller scale. Rain gardens are planted with perennials, trees and shrubs that can tolerate periods of being flooded with water, as well as dry spells once the garden drains. And because they are designed and planted as gardens, they add beauty and wildlife value to your yard!

You can see a rain garden in action down by Lucille’s Garden at Tyler. It was created in 2019 alongside the School House building and vegetable garden to capture runoff from the terrace and rooftop. It’s planted with mostly native grasses and flowers, whose deep roots help soak up the rainwater.

Whether you’re adding a rain barrel, installing permeable pavement or planting your own rain garden, we all have a role to play in solving our stormwater issues. And if that role feels small, imagine each one put together.

Picture a community where each house comes with its own rain barrel, every sidewalk and driveway is porous concrete, and the streets are lined with gardens rather than storm drains. Imagine rinsing your car on your driveway and watching the water soak down – rather than runoff. Picture watering your vegetables with stored rainwater, and watching the water from the street absorb back into the ground to nourish the flowers of your rain garden.

Like drops of water, all these solutions will come together to form something much larger and more far-reaching. Communities with failing stormwater systems can allow their water to rejoin the natural cycle, rather than flood their homes. Rivers can refill with water that runs clean. Aquatic life can return and thrive. Our children can swim and catch fish in the streams of Pennsylvania.

We don’t need to simply imagine such a reality. It exists in measurable ways, in smaller case studies across the nation, including a project that took place just about an hour from here, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

In 2011, the city of Lancaster released a Green Infrastructure Plan intended to reduce the cost of necessary repairs to their existing stormwater system. Their system, which operates the same way ours does here in the Philadelphia area, also needed to be repaired and upgraded to comply with the United States Clean Water Act – and they anticipated a similarly steep price tag for the work. So they decided to think outside the box and see how using green infrastructure, like rain gardens, green roofs and permeable pavement could benefit the city, help restore the natural water cycle, and reduce cost.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s report ‘The Economic Benefits of Green Infrastructure: a case study of Lancaster, PA’, which was published in February 2014, their creativity paid off. Across the city, their plan generated $4.2 million in energy, air quality and climate-related benefits every year, while simultaneously reducing capital costs for initial repair by $120 million in the Combined Sewer System area alone, and cutting $661,000 yearly from the treatment budget. Those are significant numbers. What can’t be measured in dollars (or at least has not been), is the quality of life improvements. This project added gardens and green spaces, repaired roads and improved parks. The community enjoyed reduced flooding – but also spaces to gather and appreciate nature.

These solutions work because they bring our communities a little closer to working in partnership with the world around us. They give each one of us an opportunity to make a measurable difference right in our own backyards – and the power to build a brighter, more beautiful, and ultimately, a more sustainable future.