Ever heard the saying, “A cucumber a day keeps the doctor away?” Probably not, but so goes the lore for the origins of the greenhouse. The story goes that the first century Roman emperor, Tiberius, enjoyed cucumbers, which come from India, as part of his daily regimen. It was an easy wish to grant during the warmer summer months when cucumbers grow in wild profusion, tangling their vines through the garden. To keep up the same productivity as the temperatures began to drop, a micro-climate of warmth was needed. The gardeners created carts with frames of translucent material to house these cucumber plants in their off-season.

A greenhouse, sometimes called a glasshouse, is a climatically controlled structure, whose walls are made primarily of some sort of transparent material regulating temperature, humidity and ventilation. Often these structures are built of glass or plastic, and this exposure to sunlight creates an internal temperature significantly warmer than the external environment. The structure of the space impedes the escape of heat, acting as a container for the warmer environment. Greenhouses can be a significant advantage, allowing us to manipulate the growing seasons determined by regional climates. And so, as gardeners we also extend our hope to nearly year-round, as we envision bountiful yields, wonderful meals and the ability to share with others. Fresh salad trimmed with beets, carrots and radishes in January? No problem.

Thankfully, over the years the greenhouse’s mission has evolved to serve a greater purpose than just growing cucumbers for the elite. Instead, the greenhouse is an important player in commercial agriculture, botanical research and at-home gardening. As an asset to any garden, the greenhouse extends the growing season. Not only are crops protected from weather patterns such as storms, blizzards and frosts, but greenhouses are a reliable form of pest protection as well.

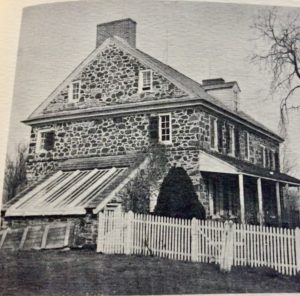

In taking a look at the greenhouses of Tyler, we first go back to the early to mid-1800s. The earliest greenhouse known to exist was present on the southerly side of Lachford Hall. While we don’t know when this lean-to style greenhouse was erected, it is specifically mentioned in writings of 1849, and perhaps goes back to 1828 when Minshall Painter speaks of the “inoculated (grafted) buds of the orange tree just taking to sprout”. The greenhouse measured 12’x15’ and was seven feet high. This photo was taken about 1870, a few years before the greenhouse was removed.

The replacement greenhouse is situated behind the Crooked Goblin Shack near Lachford Hall, and in 2021 we celebrate its 150 year anniversary. Erected in 1871, it was originally built as a pit house – the floor separating the 2 stories was added later. It was built from stone on-site in 39 days and measures 15’x28’. Minshall and Jacob Painter referred to the structure as a ‘grapery’. Forcing grapes in a greenhouse was popular at the time and while this structure may have been used for grapes, we don’t have a record stating so. We do have records noting flowers, fruit and vegetables such as tomatoes, radishes, lettuce and parsley grown during the winter months. Jacob, in particular, liked to experiment with tropical plants. In earlier years, manure was added to the basement to take advantage of the heat released as the manure fermented. In the spring of 1873, Minshall mentions “cleaning out (the) greenhouse where the chickens were during the winter”.

Dr. Wister’s photographs of the arboretum from the mid-1940s allow us to peek into the more recent past. If we go back to the early 1940s, it is apparent that Dr. Wister focused on saving this structure as the decline is obvious. A few years later, we can contrast the appearance in 1946 vs 2021. A new door, a new roof, and general upkeep is apparent, but today it looks much the way it did in 1946.

Today this greenhouse is primarily used to propagate houseplants so they are available for purchase at the plant sale and the Visitor Center. This year, Mallory Smyth from Tyler’s Horticulture team, plans to propagate some hard to come by natives, such as our prickly pear found along the path leading towards the Butterfly House. A few weeks ago, volunteers spent the morning potting up perennial plugs that will be planted in the Native Woodland Walk this spring, once they are bigger and stronger. As you can see, this greenhouse is still well utilized, long after the Painter brothers likely imagined it would be in use.

Tyler Arboretum is also home to several different forms of climate-controlled growing structures. Lucille’s Vegetable Garden utilizes some temporary hoop houses, made of steel and agricultural felt, to assist with maintaining our robust production of greens, beets, radishes and cabbage for donation. The Gertrude S. Wister Arboretum Service Facility (aka the Maintenance Building area) boasts several larger shade houses, storing and nursing woody and herbaceous species to be planted around the grounds.

Take a look at all of these structures when you visit Tyler. While they differ in so many ways, they are performing similar functions. Since it is now winter, you may especially enjoy discovering the plethora of healthy cactus and tiny houseplants seen through the glass of the old grapery. These plants could be outside in far distant southern zones, but they bask in Tyler’s imitation of a warmer place. We keep the door to the Grapery closed in the winter to retain heat…but we guarantee you’ll wish you could join them for some sun and warmth. You can almost feel the hope of a successful year ahead. It’s something we could all use a little of right now!