Our ancestors knew which trees produced food and how to use that food. Over the decades though, the gulf has grown between us and that long, deep understanding. Now, we spend most of our time disconnected from nature. Today we have to read Wikipedia or “like” a nature social media page to access that knowledge. It would not be surprising if someone a generation or two ago knew that the tree with peeling bark and pinnately compound leaves was probably shagbark hickory. Now we are in luck if a guide at the local arboretum, botanical garden, or park can take us to these towering trees, so we can gaze upon their grandeur to learn about their wondrous gifts.

That part of our history isn’t distant. It has only been in the span of a few generations that people began to suffer from ‘Plant Blindness’. When we relied on the land around us for food, water, shelter and medicine, a stroll through the forest felt very different. Our eyes saw the trees as individuals – this one gives sweet sap, this one fruit, and this one delicious nuts. This one’s bark treats coughs, and this one’s wood makes the best tools. In those days we read the land differently, and we knew where and how to find what we needed.

Much of that has changed, at least for most of us here in Southeastern, PA. Ask yourself the question – do you know the theme of this year’s MET gala? Or at least where to find the answer? The answer is probably yes. Now ask – can you find a pecan tree in the forest?

One piece of information is a part of our day-to-day lives, part of the survival – or at least an indicator of status – in our society. The other is not. At least not here, not anymore. But it used to be.

Take us back a century or two, and if asked the same question, our ancestors would have replied that they had no idea what a MET Gala was…but that they could give you directions to the sweetest nut trees in the forest. So let’s take a moment to explore some of that plant wisdom, handed down in writing of the history of some of these plants that we so relied on. Let’s open our eyes to the beauty and the function of these trees that were once so much a part of our lives.

Nut bearing trees were essential to survival no matter which continent you called home. For those of us who are from temperate climes, the easily stored nuts helped us through cold months by providing us with fuel for our bodies. They are a treasure trove of fat, carbohydrates and nutrition — exactly the sort of food you need to combat the cold of winter.

Nuts are widely documented in everyday life. An archeological dig in Israel discovered data that nuts were a substantial part of the human diet as far back as 780,000 years ago, and that some of these nut-bearing species traveled the world.

Our favorite green nut, the pistachio (Pistacia vera), started in the area that we know today as Turkey. Pistachios were consumed as early as 6850 BCE. Because of its culinary uses and as a symbol of wealth, the pistachio made it to the tables of the rich and powerful – many who conquered lands and brought the nut with them. Now it is grown in New Mexico, California and Arizona – we snack on them like peanuts. Its ready availability has cost the pistachio some of its cachet as a status symbol.

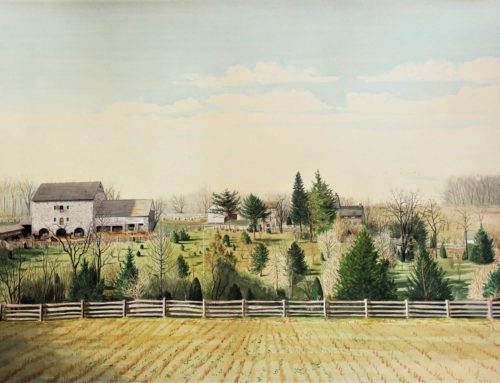

Not to be outdone, archaeologists found fossils of the native pecan (Carya illinoinensis) near the banks of the Rio Grande River which they estimate to be 8,000 years old. ‘Pecan’ is derived from the Algonquian word Pacane, which means a nut requiring a stone to crack. A pecan tree can produce nuts for 100 years, thereby providing a food source that could be relied on for generations. A grove of pecans is a good thing to have along with a vegetable garden and small livestock. Today, American pecan trees produce over 80% of the world’s crop. What would our Thanksgiving dinner be if we did not have pecan pie? At Tyler, you will find our pecan tree growing happily in South Farm.

Our native American chestnut and black walnuts were very much sought after by man and beast. According to the American Chestnut Foundation – “More than a century ago, nearly four billion American chestnut trees were growing in the eastern U.S. They were among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing trees. The wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing and building. The nuts fed billions of wildlife, people and their livestock. It was almost a perfect tree – that is until a blight fungus burned through the population more than a century ago. The chestnut blight has been called the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world’s forests in all of history.” Today, we are searching for a blight-resistant tree to hopefully bring back the American chestnut.

You either hate them or love them. The black walnut is a tree that seems to sprout everywhere, but takes will and strength to crack open the nuts. A tree of coarse texture with diamond grooved bark, this tree has a unique way of beating its competitors. Black walnuts produce a chemical called juglone which inhibits the growth of certain plants like pines, American linden and white birch. “Black walnut trees often affect the kinds and densities of plants that grow around them. Careful examination of the ground vegetation around the black walnut tree will reveal a vegetative ecosystem that is different from those found even under the adjacent hardwood trees.” (Penn State University). Traditional uses were many, from beverages to baked goods, and even as medicine for pesky worms. Like the American chestnut, animals large and small will forage for these nutritious nuts.

In a “nutshell,” humans consumed nuts, and when we traveled to new lands we brought our favorites with us. Some of these trees were competitive champions and affected the ecosystem where they flourished. Fauna such as wild turkeys feasts on acorns under a large white oak and chipmunks stuff nuts in their cheeks way beyond capacity. Our favorite four-legged animals, the whitetail deer and black bear, are known to park themselves under trees greedily consuming what falls from above. Jays, woodpeckers, ruffed grouse and wood ducks are just a few birds who are nut eaters and, of course, they prefer our native nuts. In turn, the field mice, chipmunks and others become food for owls, hawks, foxes and other predators. You see, the nut tree is just as important as fruit-bearing trees and shrubs, like viburnum or sumac. They are important for our survival, and isn’t survival status in itself?

This article is dedicated to the memory of Mike Cosgrove, Tyler Docent, Volunteer, and avid Nut Enthusiast

Photos by: Mike Cosgrove and Julia Lo Ehrhardt