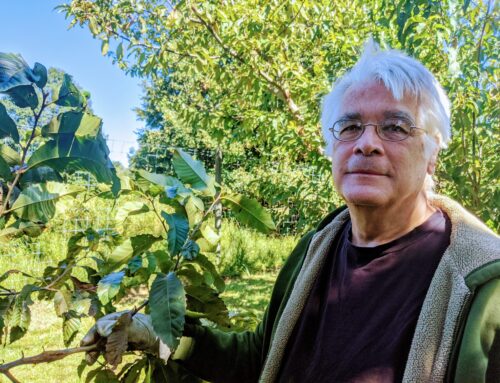

The sugar maple or rock maple (Acer saccharum) is indigenous to eastern Canada, down through Minnesota and the highlands of the eastern United States. It is a deciduous, hardwood shade tree reaching 60′ to 75′ and up to 115′ tall that can live 300 years. While the sugar maple is a prized timber tree, it also has historic and social significance for sugar production.

Sweeteners were not taken for granted in colonial times. There was no honey in North America until European colonists brought honey bees with them in the 1600s, but something sweet was already here! In 1663, the famous chemist, Robert Boyle, wrote about the tree in the new world that produced a sweet substance. John Smith was among the first settlers to remark about the Native Americans’ maple sugar processing and the fact that they used the product for barter. Maple was the easiest sugar source available to native North American people, who taught the colonists how to extract and refine the sweet sap. The other available accessible sugar source, white cane sugar, was produced on southern and Caribbean plantations and provided an alternative sweetener. In this pre-industrial period, it was economically possible to grow, process and ship this sugar north only through the use of slave labor.

Sweeteners were not taken for granted in colonial times. There was no honey in North America until European colonists brought honey bees with them in the 1600s, but something sweet was already here! In 1663, the famous chemist, Robert Boyle, wrote about the tree in the new world that produced a sweet substance. John Smith was among the first settlers to remark about the Native Americans’ maple sugar processing and the fact that they used the product for barter. Maple was the easiest sugar source available to native North American people, who taught the colonists how to extract and refine the sweet sap. The other available accessible sugar source, white cane sugar, was produced on southern and Caribbean plantations and provided an alternative sweetener. In this pre-industrial period, it was economically possible to grow, process and ship this sugar north only through the use of slave labor.

The connection between cane sugar and slavery was understood by Quakers, like the Minshalls and Painters. Using maple sugar was an act of political protest for many northern abolitionists. Honey and maple sugar became substitutes for cane sugar in recipes and drinks, and maple sugar and syrup were considered the morally correct sweetener by some in the north.

The connection between cane sugar and slavery was understood by Quakers, like the Minshalls and Painters. Using maple sugar was an act of political protest for many northern abolitionists. Honey and maple sugar became substitutes for cane sugar in recipes and drinks, and maple sugar and syrup were considered the morally correct sweetener by some in the north.

An early advocate of replacing cane sugar with maple sugar/syrup was Philadelphian doctor Benjamin Rush. In 1789, he founded the Society for Promoting the Manufacture of Sugar from the sugar maple with local Quakers. He even held a “scientific” tea party to prove the potency of maple sugar versus cane sugar.

One of Rush’s disciples in this effort was Thomas Jefferson. “What a blessing,” Jefferson wrote to a friend in 1790, “to substitute a sugar which requires only the labour of children, for that which it is said renders the slavery of the blacks necessary.” Jefferson made multiple attempts to plant sugar maples at Monticello, but the saplings died after a few years.

While the maple sugar idea failed to be widely accepted in the 1700s, the cause persisted into the 19th century. “So long as the maple forests stand,” urged a Vermont almanac in 1844, “suffer not your cup to be sweetened by the blood of slaves.”

So the next time you consider the social and ecological impact of what you purchase and consume, remember this principle has a long history in America, and maybe look to your own backyard for ways you can help with social reform.