While in college, I heard a history professor say, “America is not a melting pot – it is a tossed salad.” That observation has guided me to examine my ethnic heritage and culture, and enjoy the cultures all around me.

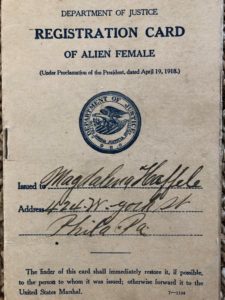

There are those among us who came to the United States for the chance to achieve their dreams. Others came out of a need to feel safe. There are those like my 2x great grandmother who came from Northern Ireland in 1848 to escape starvation amidst the potato famine. Some were taken from their homes and enslaved in America, who built a life for their family here against all odds. There are also those whose families have lived here for thousands of years, who were displaced and made to leave behind the ecosystems they knew and relied upon, and adapt to new and different climates and landscapes. No matter their reason for coming here, or their reason for leaving the place they called home, many of these cultures carried their food traditions with them. This theme will take center stage in Lucille’s Garden this year as we explore every step of what it takes to honor food tradition – as well as the many traditions that come together to create American food and cooking.

There is a deep story of resilience here; a shared kinship of arriving in a new land, with the memory of the food you cooked and ate with the people you loved. A story of people who may have been left behind or lost along the way. It takes great adaptation to carry these food traditions. You must bring the seeds of the plants you left behind, or find substitutions that will thrive in your new home. Nothing will taste quite the same. But we draw on our traditions and add ones we learned along the way because our connection to food is a powerful one. After all, we have to eat, and here in America we each bring a different sense of taste and flavor, and different foods of celebration or comfort. In other words, the world is at our table. Food from all over the world does nothing less than hold the potential of bringing us together.

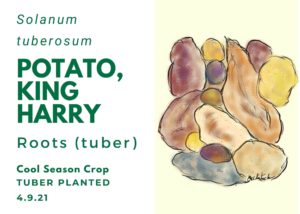

Perhaps this is because, although our food traditions come from around the world, it is all grown in the same ground. In fact, in many cases, it is the same crops, and only the applications change. Eating at a Chinese family’s home will be an entirely different experience than eating the same type of food in a home with Italian heritage. A potato will taste different in a dish from South America than it will in a dish from Northern Ireland. But we can still learn from one another, adopt new foods or different preparations. Even the way to prune and plant might change with exposure to different cultures. It’s one of the ways we come together.

Long after I said, “I do”, I discovered that my spouse’s family and my family came from the same part of Southwest Germany near the Black Forest. We both were handed down the tradition of “German” cooking, mine being more from the homeland to Philadelphia, and hers being Pennsylvania Dutch cooking by way of North Central Pennsylvania. Our families love potatoes. Three generations of my family have made “German” potato pancakes, and my wife’s family makes Pennsylvania Dutch creamed potatoes and peas. We both eat and love scrapple, and yet I eat it with ketchup and she wouldn’t think of eating it with anything but maple syrup. Part of the American story is a food culture developed through a new country with a new perspective.

Julia Lo Ehrhardt, Director of Community Engagement at Tyler Arboretum and initial designer of this year’s Asian Garden in Lucille’s Garden, has used the square foot gardening technique to highlight the plethora of vegetable types from Southeast Asia. Julia is a third- generation Chinese Malaysian whose family originated from mainland China. At age eight, her family moved to Vancouver, Canada. There, in that multicultural city, she experienced a lot of different communities, such as encountering her friend’s Italian father fermenting fruit, brought from his backyard. Fifteen years ago, Julia planted Musa Basjoo, a hardy banana, as a way to honor where she came from. While growing up, she had seen her mother take banana leaves and use them to iron shirts, giving off wax before the days of spray-on starch. She remembers to this day the smell of steam, during the announcement from the radio that Elvis Presley had died. Her Mom and Dad were big Elvis fans, at which time her mother declared, “The King has died.” And thus, now lies with her, the usefulness of the banana leaf in ironing clothes. She also wraps food in them for a beautiful presentation with its twisted end, which sits on the table like a flower arrangement, or places a leaf under a plate as an eye-striking “placemat”.

Volunteers will often taste test what is being grown in Lucille’s Garden because it makes us better interpreters of the garden for visitors. Last winter, I had a chance to sample the mizuna, otherwise known as Kyona or Japanese mustard greens. From the first bite, I was hooked. I knew come spring it was going to earn a place in my home vegetable garden. So, in March I direct seeded a half row of mizuna. Just the other day, I had my first harvest, where mizuna was showcased in my salad, on my pizza, and the next day in my breakfast omelet – yum! I am now officially the head of the area mizuna fan club. Kidding aside, I have now direct-seeded a whole row of mizuna.

One of the appeals of food is that with it we can have a feast. A feast of celebration, or of remembrance. A feast that affirms our connections, comforts us, and reminds us of the heritage we carry. A feast of foods whose tastes spark old memories, and around which we gather to create new ones. Feasts that inspire us. And so, with a basket of harvested produce, ideas, friendships, and acts of kindness we too can share a great meal. This year’s focus of Lucille’s Garden, with an eye to immigration, helps us see the banquet that is ours whenever we come to the same table, including our dinner tables.

Hope to see you at Lucille’s Garden where for three seasons (spring, summer and fall), we will feature a true feast of food, and some ideas which we hope will feed your soul and deepen your appreciation for the diversity we can experience in the place we call home.