2024. How on earth did that happen? I can’t be the only one still reeling from the shift. Wasn’t it just August 10 minutes ago? But it is March of a brand-new year, and the weather is hinting at spring.

Garden Preparations for the New Season

The garden is ready, and all traces of last year have been cleared away to make the space ready for a new season of growing. We’ve made a few changes, adjusted some of the harvest paths, and built some new wattle trellises. We’ve also made a good start on the growing season, with seedlings started indoors, all ready for early spring planting. The bulk of the work is still to come, however, and I’m enjoying this moment of peace ahead of the busyness of the growing season.

I’ve spent time this winter deciding what to grow, and where to grow it. Right now, the garden exists only in pencil and paper, a two-dimensional version of what will come. I think every gardener is familiar with this moment, excited over a new season of growing and hoping that it turns out looking at least a little the way you imagined it.

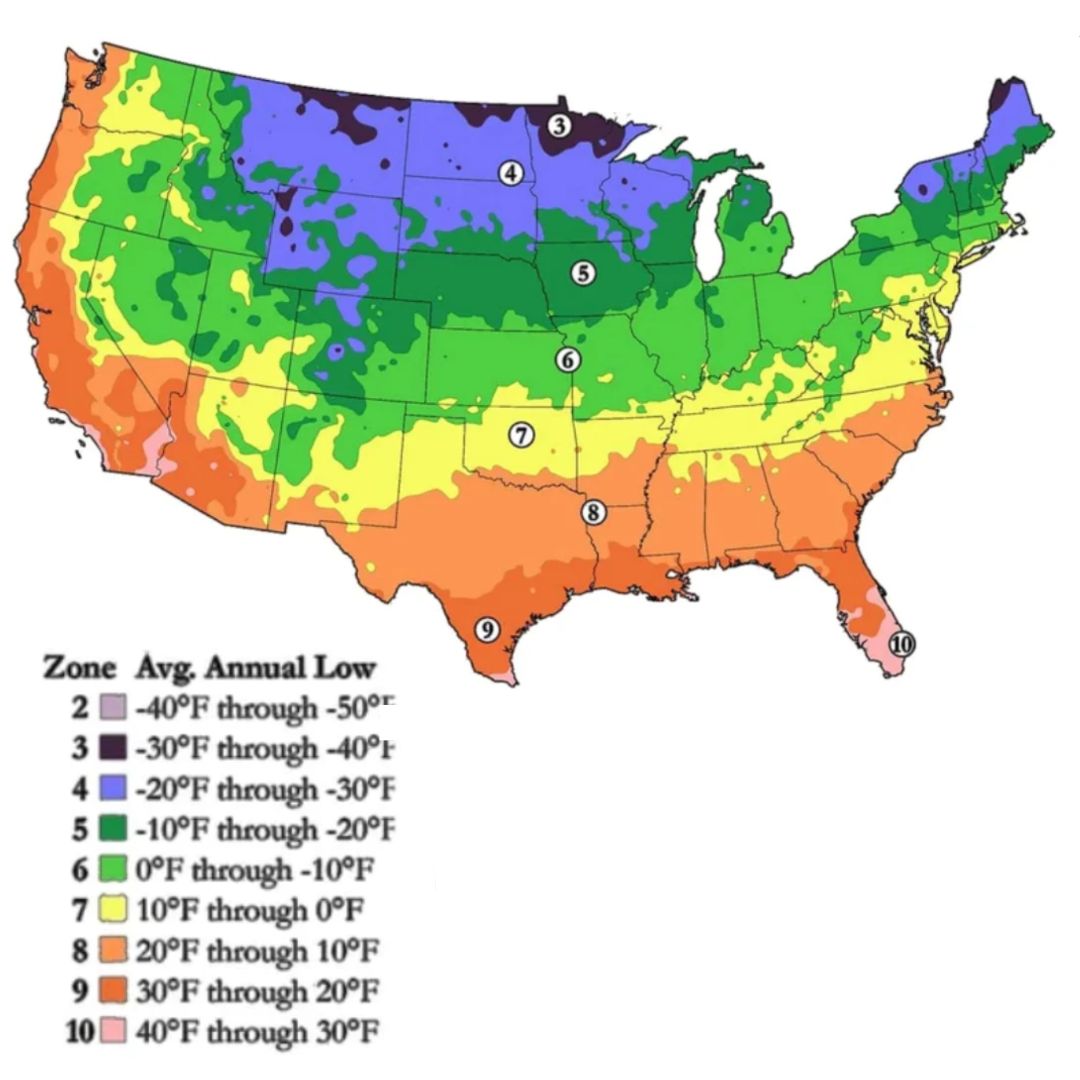

Of course, these days there is an extra level of uncertainty. Spring weather is always a little up in the air, but now, with global climate change, it’s becoming even more unpredictable. There are signs of that unpredictability across the United States, so much so that for the first time in over a decade, the USDA has updated our Plant Hardiness Zone – from Zone 6 to Zone 7.

Understanding Plant Hardiness Zones

A Plant Hardiness Zone is the official designation for an area based on average minimum temperature data. The United States, including Puerto Rico and Hawaii, can be broken down into 13 different zones, designated with numbers from 1 – 13. Each zone represents a 10-degree window of the daily average low temperature over 30 years. Way up in Zone 1 in Alaska, their average low temperature was between – 60 and – 50 degrees Fahrenheit, while down in Zone 13, Puerto Rico, their coolest window was between 60- and 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

To make things even more specific, each zone is divided into two subzones designated by the letter ‘a’ and ‘b’. Each letter represents a five-degree window within the 10-degree zone, with ‘a’ representing the cooler temperature and ‘b’ representing the warmer.

We are now in zone 7, with parts of Southeastern PA falling into 7a and parts into 7b. That means our average low temperature across a 30-year span was between 0 – 10 degrees Fahrenheit. This is a change from our old zone 6, which meant temperatures of between -10 and 0.

Adapting to Changing Conditions

This doesn’t exactly come as a surprise to the people doing the growing. We’ve all noticed a shift in the plants that thrive here. The best example from Lucille’s is our canna lilies. In its preferred zone, zone 8 – 10, canna will grow year-round. Here in Pennsylvania, to overwinter canna and grow the same plant in your garden from one year to the next, gardeners used to dig up the heavy tubers, wrap them in burlap, and shelter them indoors through the harsh winter months. However, for the past several years, our canna planting has died back to the ground in the cold – but returned each spring, re-growing from roots that stayed warm enough in the soil throughout the winter to survive.

The connection between rising temperatures and changing plant hardiness zones is not one-to-one. The new map also reflects more data – with measurements taken from 13,412 weather stations, rather than the old map, which drew from 7,983. That means this new map also reflects the increase in data.

All of this comes together to create a useful tool to help gardeners decide what will thrive in their landscape. But is it the final word on what we can grow? Not necessarily.

For example, since our zone is determined by an average of the daily minimum temperature, you can have a very mild winter that still does a lot of damage to your plants. Winter 2022 is a great example of this. That was a warm, wet season. Certainly, I remember it that way; I spent time that February winter sowing broccoli outdoors. However, that December there was a bitter cold snap, where the temperature plummeted through the course of one day and froze my rosemary plants.

Experimenting with New Techniques

So, what’s a gardener to do in this new era where the only constant is change? The answer to that is simple, even if putting that answer into practice will be complicated — we adapt. That means using all the tools and resources at our disposal, like the USDA Zone Map, and it means experimenting to see what we will be able to do next.

With that in mind, I’m trying some new things in the garden this year. The first thing I did was bring in some new soil to the garden. This soil, which is a blend of existing soil from the site, spent mushroom compost, and composted autumn leaves, was mixed, screened, and stored across the street.

On a few chilly days in February, dedicated staff and volunteers helped me wheel this soil into the garden, where we used it to raise the level of some of the beds that had sunk over five years of growing in the space. We also made some hills for crops like carrots that like loose, rich soil. In a few other places we created larger mounds that will let us grow heavy feeding crops on the top, and herbs along the slopes to reduce pests and bring beneficial insects into the garden.

Creating hills in a vegetable garden is an old practice. The hope is that the soil of the hills will warm more quickly in spring, prompting earlier germination for cool–season crops. The hills will also drain more quickly, which is helpful as our storm events bring more and more rain. The loose soil of the hill also allows crops like carrots to grow straight down and potatoes to stretch their roots and produce more tubers.

I took advantage of the soft rain we saw at the end of February to seed carrots and beets in our newly created hills. We built a quick wind tunnel with freeze cloth and metal hoops to cover the delicate seeds and keep them from freezing. Then we let the late winter rain do the rest. Those seeds, sowed on February 22, were the first planted outdoors in the 2024 season. My hope is that this, combined with some cold hardy seedlings started indoors, leads to an early start to the growing season.

Optimism Amidst Uncertainty

What will these changes mean for the garden this year? I don’t know. I likely won’t know until next fall, when the dust settles. So much of gardening is an experiment; reflective of the gardener asking what will happen if I do this? Still, the process makes me feel hopeful. Climate change may be creating instability, both in our communities and our gardens, but we can grow and adapt.

Stop by for a visit next time you’re at Tyler. I would love to hear from all members of our community about your thoughts on our zone shift and about what you’re doing in your own gardens. If there’s one thing I like to do, it’s to talk about plants. The growing season is almost upon us – so here’s to a season of beauty, learning, and – of course – delicious produce.