Exploring the Enchanting World of Mosses at Tyler Arboretum

Welcome to the miniature forests beneath your feet – the world of mosses, those often overlooked and underestimated wonders of nature. At Tyler Arboretum we invite you to embark on a journey through the enchanting realm of mosses. These tiny land plants, the tiniest in the world, play a vital role in our ecosystem and contribute to the rich tapestry of our natural heritage.

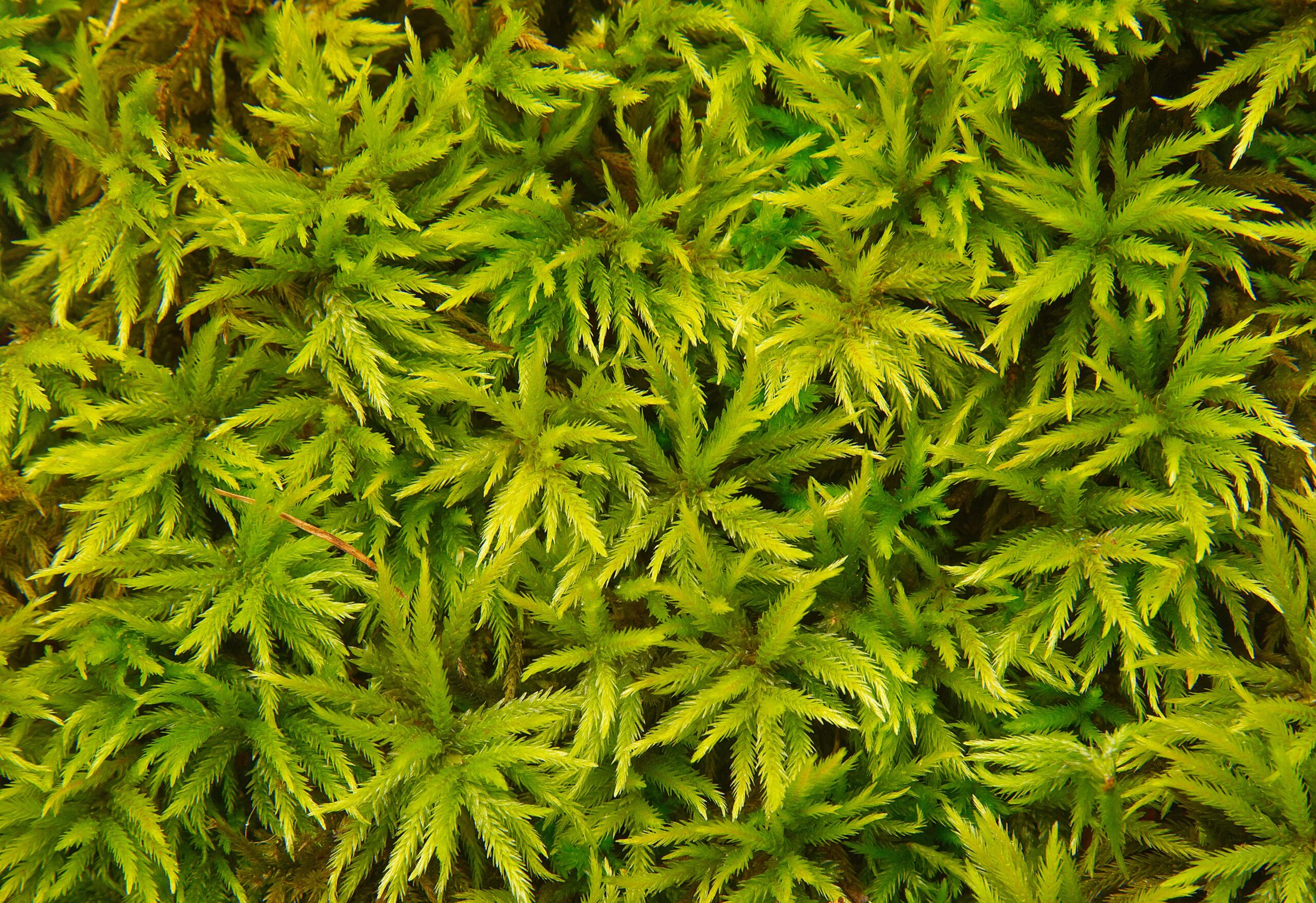

The Moss Bank at Tyler Arboretum: a miniature forest (Photo courtesy of Barry Rubin)

Discovering the Moss Bank

Head down to the moss bank along Rocky Run in the Old Arboretum, just before you cross the bridge near Painter Road. Here, a peaceful tapestry of native mosses awaits, thriving naturally in the shade and moisture. Unlike traditional landscaping, we’ve embraced the mosses that were already present, removing invasive grasses and weeds to reveal a lush green carpet. About ten native moss species, along with a touch of liverwort, now weave together to create a stunning display.

Feel free to explore this living canvas, as mosses serve as miniature forests, providing habitat for insects and microscopic organisms crucial to the ecosystem’s food web. Walk gently, crouch down for a closer look, and if you find patches disturbed by curious creatures, tuck them back in place.

Tip: Enhance your moss-viewing experience by using your phone as a magnifying glass. Capture photos and zoom in to unveil the intricate details of these tiny wonders.

The Ecological Roles of Mosses

Mosses are often likened to miniature forests, offering moisture and habitat for insect larvae and microscopic organisms that play crucial roles in the ecosystem’s food web. These resilient plants are pioneers on bare soil sites, where other plants struggle to grow, contributing to the buildup of organic matter in the soil and creating a more habitable environment for successional species. Additionally, mosses help prevent soil erosion by slowing water runoff after heavy rains.

Ongoing research is delving into the intricate interactions between mosses and the forest’s microbiome. Mycorrhizal fungi mats found under moss beds are thought to benefit from the consistent moisture provided by mosses, potentially enhancing nutrient uptake by surrounding tree roots. Mosses are also actively involved in regulating nutrient flow through the ecosystem by absorbing nitrogen that would otherwise easily leach through the soil and enter our streams. This unique capability makes mosses a subject of interest in bioremediation projects.

Moreover, mosses are being studied as indicators of environmental quality. Their direct absorption of nutrients through leaves makes them particularly sensitive to air and water pollution exposure. Certain moss species’ presence or absence can signify the environmental quality of a given area, akin to using aquatic organisms as indicators of water quality.

Anatomy and Reproduction of Mosses

In contrast to most familiar plants, mosses lack roots and veins for water transport. They absorb water and nutrients directly through the surface of their leaf cells. Reproduction occurs through spores and plant fragments that break off and disperse, contributing to the widespread distribution of mosses. Observant visitors may notice spore capsules growing above a moss plant on the end of a thin stalk, each capable of releasing hundreds of thousands of one-celled spores into the air currents. Fortunately, mosses are non-allergenic for humans.

The ideal time to observe mosses is after a refreshing rain. The leaves unfurl and capture water as a surface film to absorb directly into the leaf cell. During dry spells, mosses enter a sort of short-term dormancy, halting photosynthesis and growth until water returns.

Moss can be particularly vibrant after a rain

Meet the Mosses

You’ll find the moss species listed below at the Rocky Run moss bank. While fern moss (Thuidium delicatulum) dominates the site, you’ll also encounter small patches of these other mosses thriving alongside lichens and liverworts.

Click on any thumbnail below to access a slideshow with more detailed photos.

Beyond the Moss Bank

If you’re eager for more moss exploration, venture beyond the fence.* Look for mosses along exposed trailsides, rocks, tree bases – anywhere flowering plants have trouble establishing. Just outside Gate 1, off the Blue Trail, two large moss mounds near Rocky Run showcase examples of all the mosses listed above. As you continue along the Blue Trail, keep an eye out for exposed mounds where mosses take advantage of higher spots where winds blow away leaves. In these beds, small wildflowers like partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) and spotted wintergreen (Chimaphilla maculata) thrive, taking advantage of the freedom from leaf litter cover.

Mossy Run

Before the Blue Trail enters the Middle Farm field, Mossy Run below on your left, trickling out from the old spring house ruin, provides a perfect environment for the emerald green moss Brachythecium rivulare (waterside feather moss) to thickly cover the stones. Its vibrant green stands out, especially when snow blankets the surrounding area. Atrichum angustatum (star moss) is also noticeable on the root stump of a fallen tree by the Blue Trail past the Purple Connector. As you reach the Indian Rock area, keep an eye out for Anomodon attenuatus (tree skirt moss) growing at the base of the trees by the water and on the giant boulders.

*Hiking trails outside the 100-acre fence are temporarily closed while ash remediation work is underway. Learn more.

Anomodon attenuatus (tree skirt moss) growing near Indian Rock

Moss bed outside of Gate 1

Mosses in the Garden

The appeal of mosses extends beyond woodlands and into gardens, adding a touch of antiquity and serenity. Japanese gardens are renowned for their use of mosses, a practice echoed closer to home at Mt. Cuba Center, Bowman’s Hill Wildflower Preserve, and Chanticleer Garden. Many of these mosses arrived naturally and were nurtured over time, emphasizing the challenges of transplanting mosses due to their specific niche requirements for humidity and preferred substrate.

Contrary to their reputation as lawn weeds, mosses in lawns signify environmental conditions which inhibit grass growth and favor mosses. Grass struggles in heavy shade, poor drainage, compact soil, and acidic conditions, and mosses fill in these spaces where grass fails to thrive.

MOSS FUN FACTS

- Beyond their visual appeal, mosses serve as acoustic panels on the forest floor, creating a sense of stillness and peace. The same air pockets designed to capture and conduct water along the plant surface also function to absorb sound, contributing to the serene atmosphere of forest spaces.

- Mosses grow slowly, with a moss mat expanding only by 1/4″ to 1/2″ per year. Penn State Extension estimates that if half of a large moss mat on a fallen log were removed, it would take 20 years for the mat to fully regrow. Therefore, while observing mosses, it’s crucial not to disrupt their delicate ecosystems by scraping up large patches to take home.

- There are over 15,000 moss species worldwide (and more to be discovered). Pennsylvania has over 400 documented species of moss. Delaware County has just under 100 documented species. (Western PA Conservancy, 2023)

- Mosses belong in a group called bryophytes, along with liverworts and hornworts. Bryophytes were the first plants to evolve on land from green algae over 400 million years ago. They were here before ferns, conifers, flowering plants and before dinosaurs!

Further Reading Suggestions

For those intrigued by mosses, delve deeper into their world with the following recommended readings:

- Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses by Robin Wall Kimmerer (Highly recommended)

- Native Ferns, Mosses & Grasses by William Cullina

- Outstanding Mosses & Liverworts of Pennsylvania & Nearby States by Susan Munch

- Common Mosses of the Northeast and Appalachians (Princeton Field Guide) by Karl McKnight, Et Al.

This project is a collaborative effort between Alison Dame, a participant in the PA Master Naturalist program and Tyler Arboretum. Special thanks to Linda Coulston (Tyler Volunteer) and the Hort Staff for their assistance.

Photos courtesy of Barry Rubin, Alison Dame, and Dave Charlton.