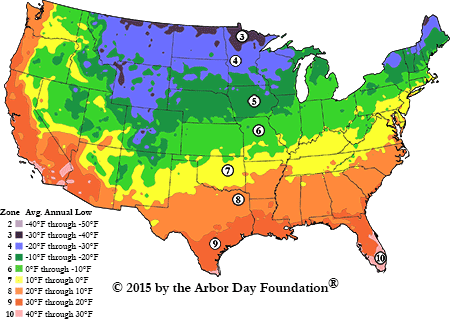

As climate change occurs, our gardening practices must adapt. By the end of this century, scientists predict the hardiness zones may become one to two zones warmer in any given area. Right now, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, is somewhere between zone 6b/7a, but in just three generations, we expect to see that shift to zone 8b/9a – closer to the current climate of Virginia and North Carolina! And in fact this doesn’t even tell the whole story. ‘Hardiness’ zones refer to the coldest temperature a plant can tolerate. In the mid 1990s the American Horticultural Society introduced a ‘Heat Zone’ map that reflects the hottest days in each region. Just as certain plants are adapted to survive down to different temperature lows, different plant species have evolved to tolerate different heat extremes as well. So, with projected warmer winter temperatures, high and more severe rainfall events, and more days where the temperature exceeds 86 degrees Fahrenheit, what’s a gardener to do?

Images courtesy of the Arbor Day Foundation

We can expect to see a shift in the plants we can grow. We may be able to grow frost-tender plants through the winter, and wetter weather may make it more challenging to grow tuberous plants that depend on good drainage. Cold-hardy plants that require a chilling or dormancy period could suffer from temperature change. We may lose species that cannot tolerate days of extreme heat.

As the temperature warms, it will affect birds, insects, and plants. Pests usually killed by colder weather may survive at higher rates. Since many animals depend on flowering and fruiting for food, climate changes can alter these animals’ foraging and breeding patterns.

Another troubling part of climate change for gardeners is that weather patterns will not just become warmer in the future but will become increasingly extreme and erratic. The prediction is for more intense and longer-lasting droughts and more extreme heavy rainfall events. Some scientists have also suggested that climate change may result in instability in jet stream patterns that could increase the frequency of polar vortex events, such as those that produced record cold temperatures in 2014, 2015, and 2019.

The projected increased variability in future weather patterns is a daunting challenge for many gardeners. If only we had to contend with consistent, gradual warming, we could simply borrow plants from our southern neighbors. The problem is this – plants don’t respond to averages; they respond to extremes.

To get right to the point, gardening amidst climate change involves managing risks. Like managing other types of risk, diversity is the best tool gardeners have for dealing with climate change.

Here are some ways that gardeners can respond to climate change:

- Be mindful of your energy consumption, which will lower carbon emissions, the cause of global warming. For example, cut down on gas-powered tools and fossil fuel-based fertilizers.

- Use regenerative garden practices, like no-till gardening by using a fork or hand-turning your garden instead, composting, and careful plant selection to enhance ecosystems and enrich soils.

- Plant trees. Deforestation contributes to the “greenhouse effect.”

- Plant diversity is the key to sustainability – to ensure good harvests and withstand diseases and pests. For example, if drought or disease attacks one variety of tomatoes in your garden, a different tomato variety may easily survive those same conditions.

- Plant a polyculture of many different crops and species.

- Plant edibles, herbs and flowers in the same beds. Flowers and herbs act as companion plants and attract beneficial insects and bees.

- Plant several varieties of each crop. Old-time heritage and heirloom varieties offer unique qualities like superior taste or resilience under varied conditions.

- Rotate your crops to prevent disease and soil depletion caused by planting over and over in the same spot. Different crops add or take away different nutrients from the soil.

- Include native plants in the landscape of your yard. When a native plant habitat is present, all the benefits of generations of beneficial coexistence are available to your garden.

- Build microclimates by taking advantage of natural features such as shade trees, mulch, raised beds, and barriers such as cold frames and hoop houses to mitigate plant exposure.

- Save seeds because when you do, you are selecting the best traits of your healthiest plants and preserving them for the coming season. Choose open-pollinated plants (called heirlooms, heritage, or open-source), as seeds from patented hybrid plants cannot be saved because they will not reproduce true. Grow out your plants until they flower and set seed. Lettuce, peas, beans, tomatoes, and grains are easy vegetables for seed saving. Saving seeds ensures your food security. When local stores have shortages (as they may increasingly have when droughts and other events cause interrupted supplies), you will have seeds to plant and garden vegetables on hand to fill your plate.

- Plant cover crops for fall and winter vegetation to prevent erosion and runoff, keep carbon dioxide in the soil, maintain soil structure, and feed the soil.

- Incorporate compost into your garden. Consider compost as food for soil microbes that make nutrients available to plant roots. Organic matter improves soil health, creates and maintains good soil structure, retains water, and sequesters carbon.

- Cover soil with mulch. Spread organic mulch to prevent erosion, moderate soil temperature, conserve moisture, and reduce weeds. As mulch decomposes, it becomes compost and feeds the soil.

- Eliminate chemicals. Use Integrated Plant Management (IPM) to maintain a healthy garden. Insecticides kill pests as well as beneficial insects. Toxic chemicals find their way into waterways and groundwater. Chemical controls may be quick and easy but counterproductive in the long run.

- Minimize fertilizer. Nutrients remain in decomposed organic matter in the soil until plants need them. Compost is all the food our soil needs to support our plants, and excess inorganic fertilizers are easily leached from the soil and pollute our waterways.

As gardeners, you know what Ernest Hemingway said is true, “The Earth is a fine place and worth fighting for.”

So, let’s take hold of the tools that will bring about change, beginning with our own gardens – our composters, mulches, cover crops, forks, hoops houses, raised beds, and saved seeds. Will you join Tyler Arboretum and me in the fight for our planet through the means of strategizing, adapting, mitigating, and regenerating? Together we can make a difference.