All around us, every day, the land we call home changes. Old buildings come down or are repurposed. New houses and roads go up. Old trees vanish, and new ones appear. The landscape is not a constant thing – it changes slowly, but it grows and evolves with each alteration.

Still, there are clues left behind of what it looked like before — artifacts of an ancient story. The legacy of the land can be found if we pay attention and know how to look. We’re lucky at Tyler to steward one such artifact –The Serpentine Barrens at Pink Hill, a living remnant of a story that goes back thousands of years.

These Barrens, the only site remaining of the ten that graced Delaware County, is a piece of a unique and ancient ecosystem – the Eastern North America serpentine grasslands. Grasslands are unusual here; they are much more common in places with lower rainfall. So what keeps trees from moving into areas like Pink Hill? The answer lies in the site’s bedrock – and reaches back into the earth’s earliest history.

The bedrock underlying Pink Hill is serpentinite, a pale-green metamorphic rock found in abundance beneath the oceans but rare on land. Formed only in the deep sea, it can be pushed up onto the continents in the chaos that ensues when the Earth’s tectonic plates collide, as is happening right now at the Himalayas and Andes. Most of North America’s serpentinite bedrock is in scattered slivers near the East and West Coasts, where the continent’s geologic history was most chaotic. The area we call Pink Hill is a vestige of three cataclysmic collisions that created giant mountain ranges with chunks of serpentinite in their cores. Hundreds of millions of years of rainfall wore those mountains down to the low, gentle hills of our Piedmont landscape, finally exposing the serpentinite at the surface.

This serpentinite’s effect on the soil wouldn’t immediately be obvious if you were to pick up a handful of barren earth in your hand. It feels like good, moist agricultural soil. But it has an invisible secret. The serpentinite is soft and weathers easily, forming a soil that contains high levels of magnesium, nickel, and chromium. But unlike more ordinary soils, it contains very little calcium. The imbalance of extremely low calcium and high magnesium, together with high levels of nickel, can prove toxic to plant life.

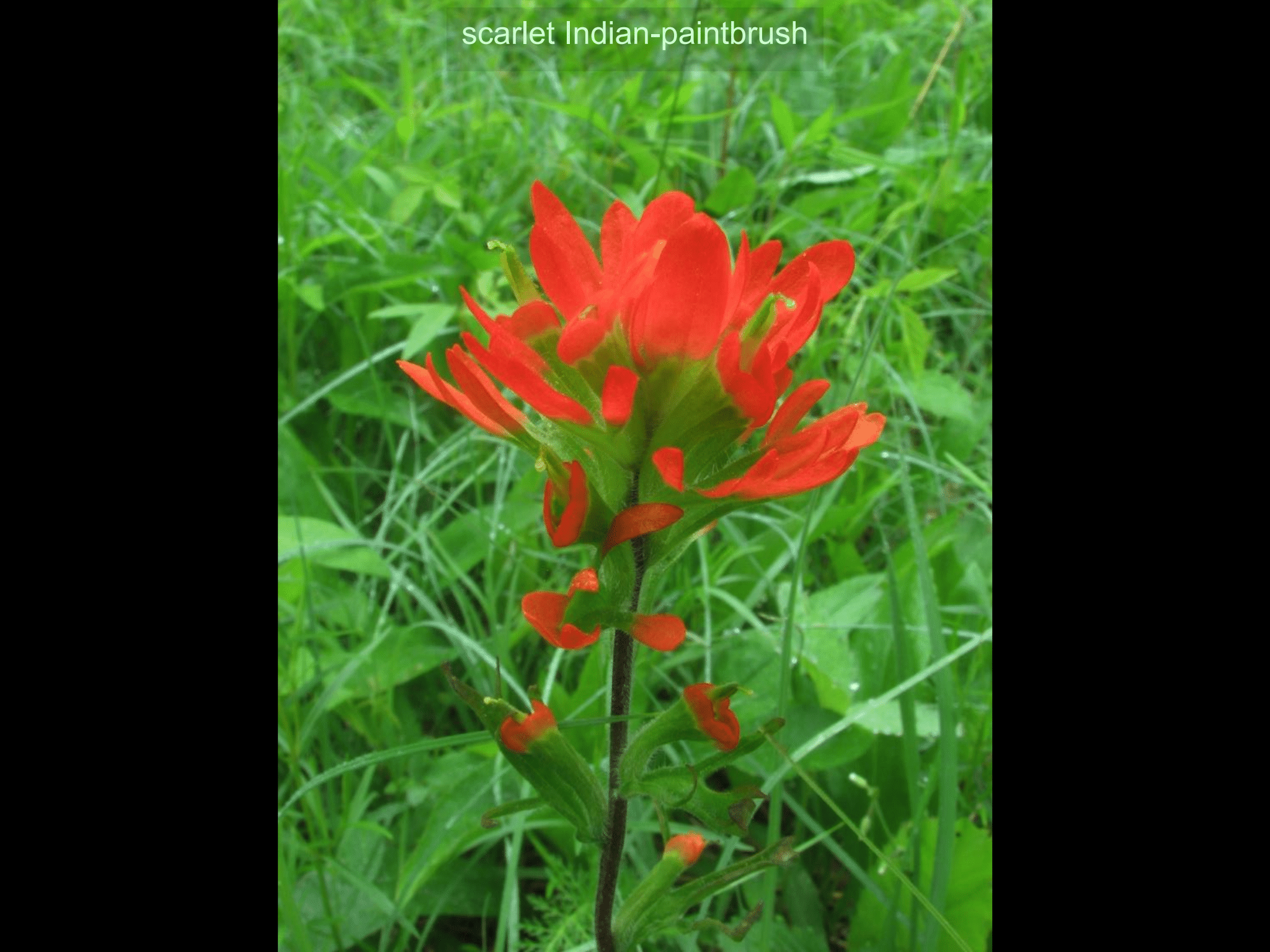

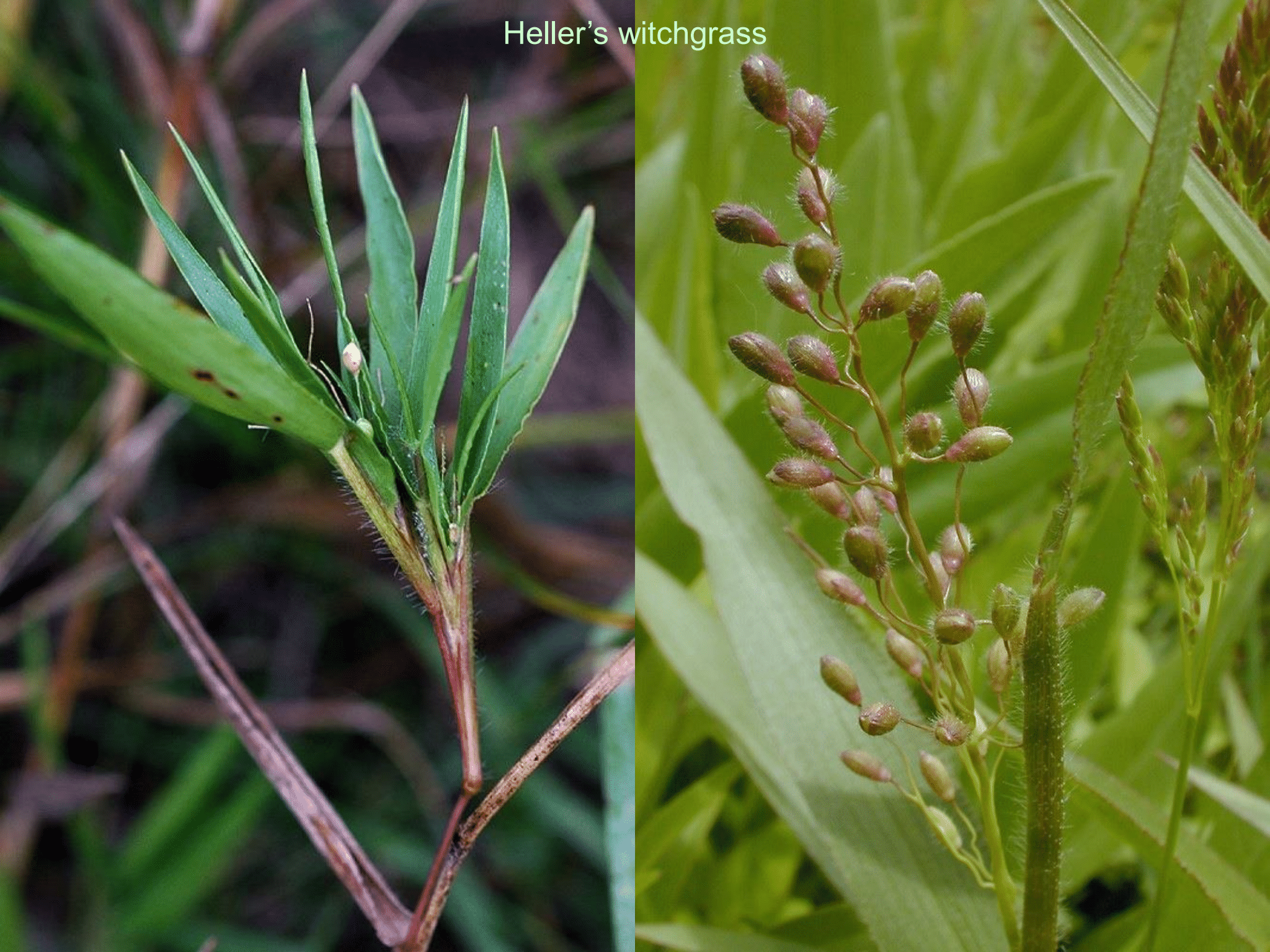

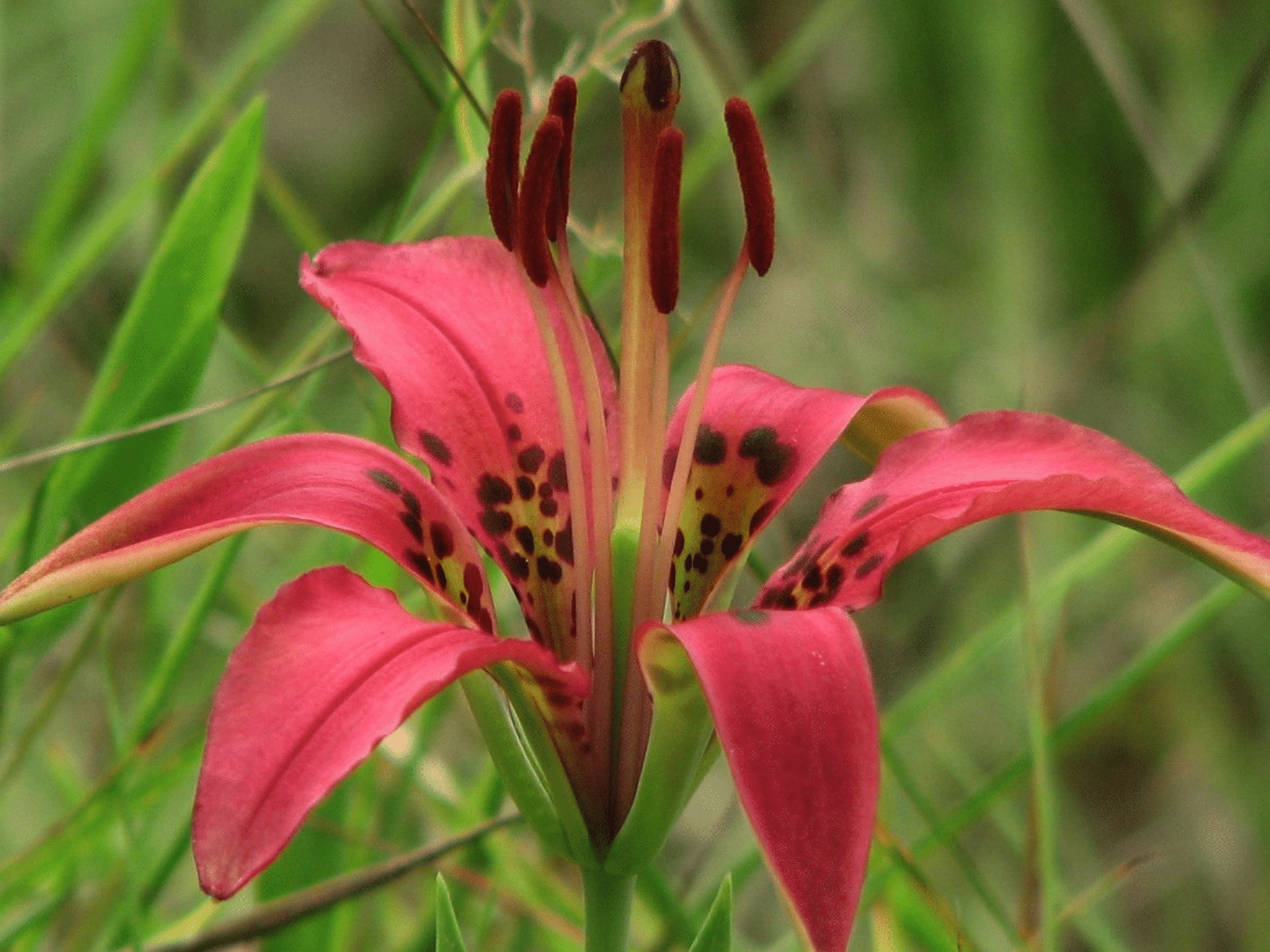

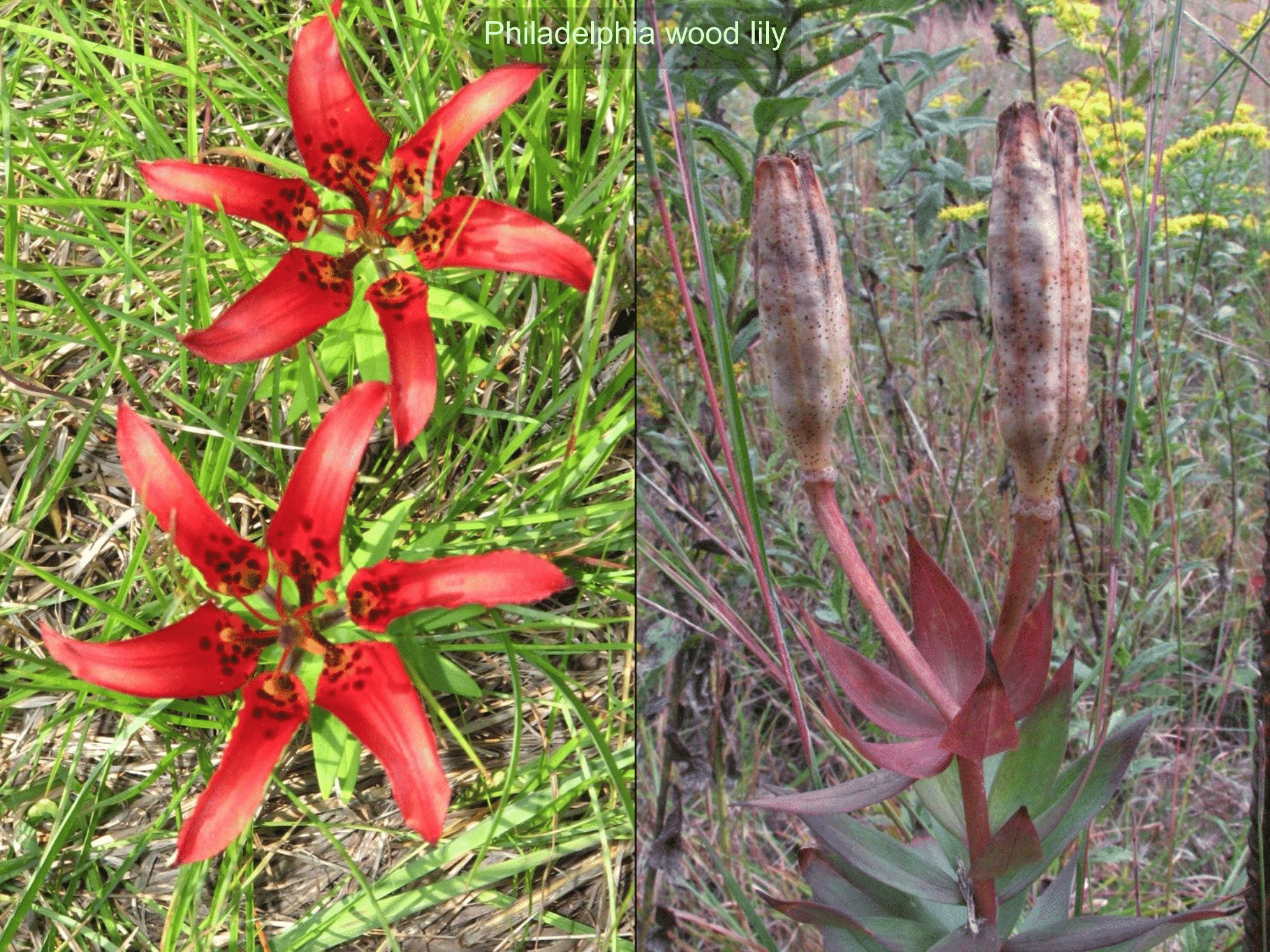

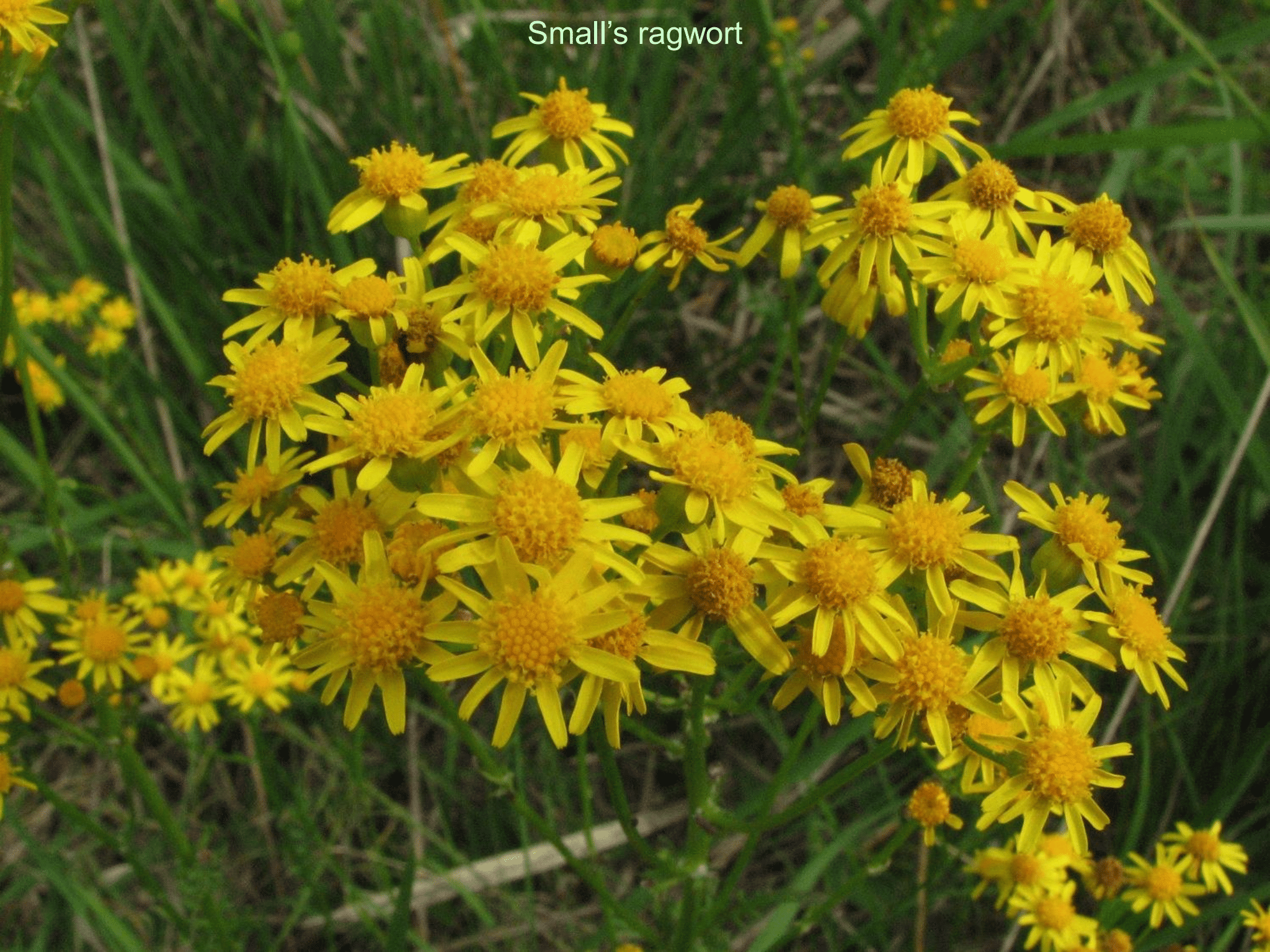

Of course, if you were to take the Pink Trail at Tyler and hike out to the Barrens, you’d find that it isn’t barren at all – it’s carpeted in grasses, wildflowers, and even a few small trees. The historic open portion of Pink Hill is home to the endemic and often rare species of plants that can sustain themselves in serpentine soil. Some of these species, like the serpentine aster (Symphyotrichum depauperatum) and arrow-feather three-awn grass (Aristida purpurascens), are listed by the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program as Threatened, and the serpentine aster is found only in serpentine barrens. Other species found at Pink Hill, like little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans), are stunted and small. These species can grow fast and tall in the meadows at Tyler, but at Pink Hill, they take a more conservative approach. They grow slowly, never reaching their full height, forced to conserve their internal resources so that they can survive in the harsh soil.

The unique species gives Serpentine Barrens their special character – that of an open grassland ecosystem. However, even with the difficult conditions, the open grasslands couldn’t have persisted without periodic disturbances. Plant growth in the Eastern United States tends toward temperate deciduous forest, or mixed deciduous conifer forest, as you can see along many of our other Tyler trails. Eventually, over thousands of years, organic material from the surrounding area should have built up enough of a buffer that the soil at Pink Hill would be able to support other plant and tree life. So, what were the disturbances that kept this area as grassland?

In ancient history, it was large herbivores. Elk grazed the grasses of Pink Hill, and before them mammoths, the black-bear-sized giant beaver, the stag-moose, giant horses, and giant ground sloths. The largest of them pushed over adult trees to eat the leaves and tender twigs and most ate seedlings while grazing, causing large areas to remain treeless. So when you hike out along the ridge at Pink Hill, you follow in the footsteps of ancient, now extinct, megafauna. Imagine, the next time you visit, the shaggy brown back of a giant beaver at the foot of one of the black-jack oaks or the massive bulk of a mammoth grazing at the base of the hill.

The disappearance of these creatures occurred at roughly the same time that people arrived on the scene in North America. Humans took over the disturbance cycle and kept the grasslands open through burning. Later, haying and grazing largely displaced fire in our area, leaving us with today’s open land.

There are plenty of questions surrounding the Serpentine Barrens at Pink Hill. We have no way to know for sure how old the open portion of the Barrens is. Based on the exceptionally high species diversity, we can make an educated guess that it is very old, on the order of thousands of years. Likewise, we have no written evidence of Native American burning practices at Pink Hill. However, what we know from historical records, pollen analysis, and ecological succession in our area point strongly to the conclusion that Pink Hill is an artifact of historic fire-management practices by the Native people.

So what happened next? The story of Pink Hill from the 1700s on is neither unique nor new. The indigenous tribes were displaced by settlers who wanted the land for agriculture. In our area, this means the Lenape. A large portion of the tribe was forced out or fled and dispersed throughout the country, but some remained and are now in the process of revitalizing their communities and practicing their traditions. For more information about the Lenape Nation, you can visit the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania website Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania. To learn more about native lands worldwide, and particularly in our area, see this digital Native Lands Map.

With European settlement, burning at Pink Hill stopped. As we know, the land was owned by the Minshall/Painter family, and slowly the forest around Pink Hill began to creep in. The surrounding forest deposited leaves year after year, enriching the soil with decomposed organic matter and allowing tree seeds to germinate. The Serpentine Barrens at Pink Hill shrank, following the path of other barrens in the area, and running the risk of closing in altogether, shading out all the sun-loving species that make the barrens unique.

Still, the story of Pink Hill is one of a legacy of good luck. Many of the Serpentine Barrens which were in Delaware, Chester, and Lancaster Counties, Pennsylvania, and Cecil, Harford, and Baltimore Counties, Maryland, were mined for minerals, that occur in high quantities in serpentinite. The Minshall/Painter family quarried at the edge of Pink Hill, but the Barrens were left mostly intact. Pink Hill was also never plowed, a real rarity in southeastern Pennsylvania. This left the fungal ecosystem of the Barrens undisturbed, which helps to support the high diversity of serpentine plants and will, hopefully, be a leg up in the restoration process in the newly opened part of the Barrens. The family grazed cattle on Pink Hill, which likely helped keep the grassland open, even though the livestock certainly deposited their own organic matter.

Pink Hill was once one of ten open Serpentine Barrens in Delaware County. And it gradually shrank from many acres of open grassland when title to the land was granted by William Penn, to just 2.5 acres in 2018. But the Arboretum has been a leader in preserving this unique and rare habitat.

“Tyler is the pioneer in Serpentine Barrens Management. It is the first place where fire was applied to manage Serpentine Barrens,” says Dr. Roger Latham. This first burn may have occurred on the advice of Edgar T. Wherry, an American Botanist who lived from 1885 to 1982. In the 1970s, 20 years before fire was more widely adopted as a management practice, Arboretum staff began burning portions of the Barrens. The Middletown Township fire companies took over the practice in the 1980s, continuing the burns as a training exercise. In the 2000s the Arboretum began contracting with prescribed fire crews who have specific expertise in ecological stewardship burning. The most recent burn occurred in 2016.

Tyler also tested the efficacy of soil organic matter reduction (also known as “scraping”), essentially coming through with a backhoe or front end loader to remove the upper layer of new organic material and expose the serpentine soil beneath. In the early 2000s, several test scrapes were completed, an experimental process intended to see what species, if any, would return. According to Dr. Latham, the results were “totally amazing…not a single invasive species came in at Pink Hill. They just became classic serpentine barrens.” This is because the high mineral content of the native soil cannot be tolerated by non-native species and any invasive plants that do germinate drop out of the population.

Where did the species that appeared on the scrapes come from? From years of deposited seeds present in the removed soil and seeds blown in from the ancient, still open portion of the Barrens.

The success of these scrapes inspired the largest restoration project done on Pink Hill to this day – the large-scale removal of organic material and re-seeding process that took place starting in 2018. This project added seven acres to the Pink Hill grassland, almost quadrupling the open area of the Barrens.

This is an ambitious undertaking. Tyler removed trees and layers of organic material to expose the ancient soil of these newly opened acres. Partners from nearby Mt. Cuba Center came out to survey the area with Tyler Plant Records and Horticulture Staff to transplant the native forest orchids that were found on the site so that they could grow them in their greenhouse and plant them out. Horticulture staff and volunteers collected seed at the nearby Sugartown Barrens in Chester County to help reseed the newly scraped area at Pink Hill and increase the genetic diversity present on the site.

What have we seen so far? According to Dr. Latham, “The restoration process is coming in great. If you were to do bulldozing in Pennsylvania anywhere but on Serpentinite, you’d get lots of weeds. The restoration site is still fairly low in diversity of serpentine grassland species, but there is little ‘invasive’ species cover and it appears to be declining. There’s actually a higher number of native species than was present on the ancient barrens, though some of those will drop off as the serpentine species outcompete them.” So, we’re encouraged by the results so far.

Still, there’s more to be done. As we explored earlier, Serpentine Barrens are artifacts of disturbance. Therefore management through fire, will need to be a part of the plan for Pink Hill moving forward. The next burn on portions of Pink Hill will take place this spring, sometime in the coming weeks, when conditions allow it to be done safely. This restoration project is a grand experiment. What will return to the newly opened area of the Barrens? Will we find, once again, the rare or endangered species that bloomed in those fields when the Minshalls arrived on the property?

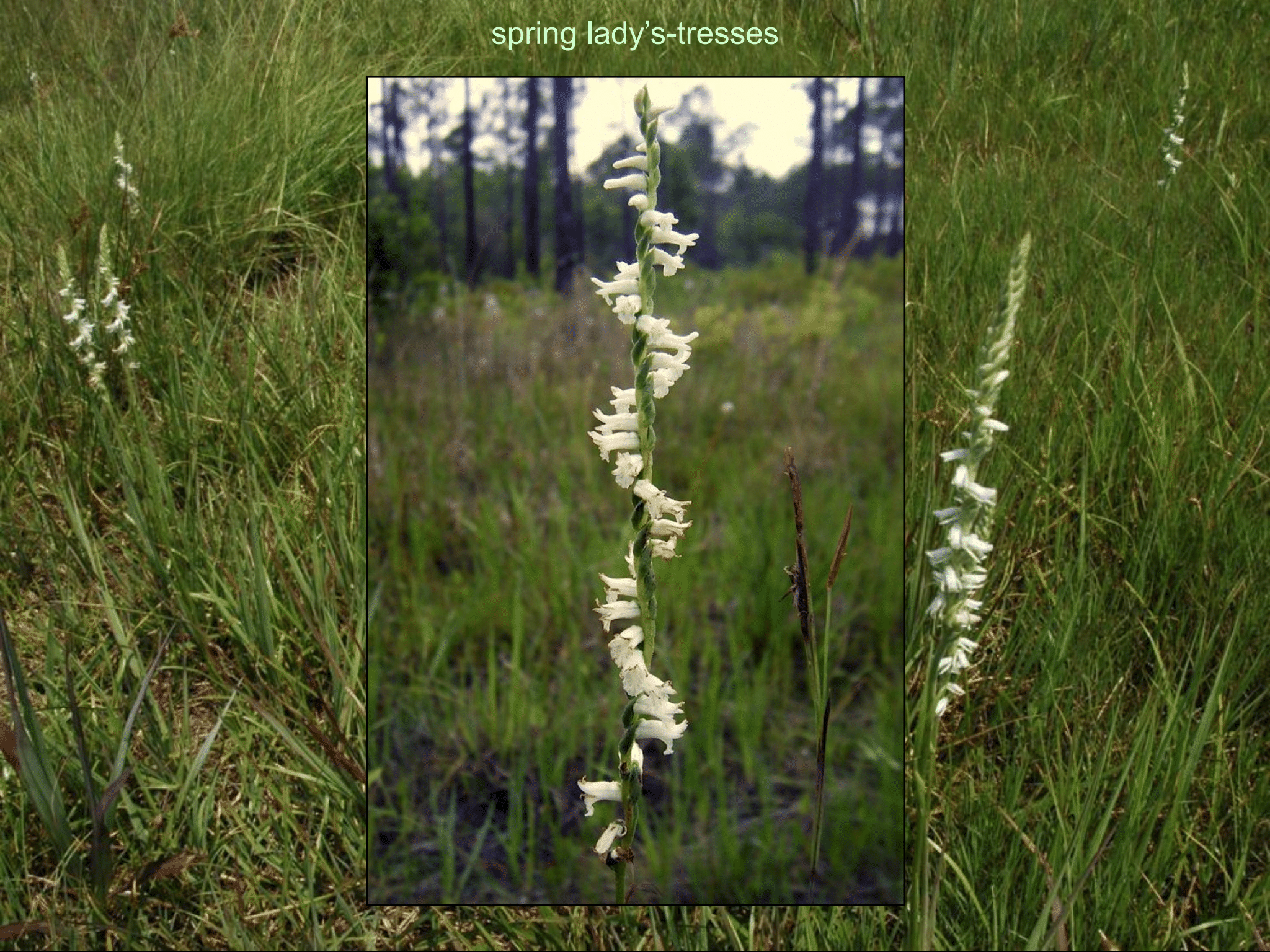

We hope so. The return of plants like colic-root (Aletris farinosa) and spring ladies tresses orchid (Spiranthes vernalis) would mark an incredible achievement. We have a responsibility to make sure these species, which we know from surveys historically grew on Pink Hill, have a chance to grow there once again.

The legacy of the Serpentine Barrens at Pink Hill is one of deep history. It shows us in the landscape the influence of the underlying geology and the imprint left by the megafauna that once grazed here. It reminds us of the heritage of the Lenape, who stewarded this land for thousands of years and continue to call it home. It is also a legacy of exploration and a pioneering spirit to experiment in the natural world that was a part of the Minshall/Painter family’s home and legacy.

What will happen next is the legacy we’ll leave for the future. Our goal is that Pink Hill will be a place of high serpentine grassland species diversity. — a treasure trove of rare and endangered plants that will again grow wild in the unique soil. It will take hard work, but we can watch the regrowth together.

Join us this spring and summer for one of the Pink Hill Tours we have planned; find the next one on our calendar. Or stop by on your next hike at Tyler and take a moment to reflect, both on the history you can read in the land and the future we get to see unfold.

Take a look at the gallery below for a sample of just some of the special plants that you can find at the Pink Hill Serpentine Barren at Tyler. All photos are courtesy of Dr. Roger Latham.