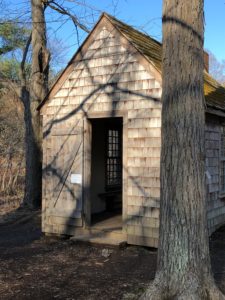

Every time I go to Tyler Arboretum, I step inside the replica of Thoreau’s Walden cabin. That’s the way it has been for me this past year, and I ask myself, why? Could it be that eight generations of my family beginning in 1630, have lived in Concord, Massachusetts which has been home to such greats as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Nathaniel Hawthorne – all of whom I love? Could it be that Thoreau was born and then spent his boyhood in two houses owned by my descendants the Wheelers and Minots? Could it be that what he wrote at Walden Pond and what he did there profoundly speaks to our time? The answer is yes, yes, and yes!

In March 1845 Thoreau decided to build a cabin by Walden Pond on the land of Ralph Waldo Emerson in Concord, Massachusetts, so he could conduct a so-called “personal experiment.” He describes his pursuit at Walden this way: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Tyler Arboretum is my Walden. I go there so I may come back with a greater commitment to being intentional about how I live in the world, more focused on what really is essential, and what can and must go in my life if I am to really live and not just merely exist. I guess that is why I step inside the cabin during every visit – to remind myself of what is important, and to ever deepen the values I hold dear and the world so desperately needs.

My heart resonates and even revives when I remember some of the things Thoreau wrote while at Walden, such as “not just being good, but being good for something and the question of “what is the use of a house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it on and “there are moments when all anxiety and stated toil are becalmed in the infinite leisure and repose of nature.”

For Thoreau, nature was a communicating consciousness, and he wanted to make himself available to it, antennas raised. Full receptivity required removal from ego-driven clamor, which was how, in his most stressed moments, he viewed human discourse.

In addition to observing nature, Thoreau used his semi-seclusion at Walden to pursue an intensive course in self-education, one that required undistracted reading. The list he compiled was long, ambitious, and culturally far-reaching, stretching from classical Greece to Vedic India.

Finally, last but not least, Thoreau used his time at Walden to clarify his political thinking. It was while living at Walden that he spent a night in jail for refusing to pay taxes that he saw as contributing to a warmongering, slavery-supported government. At Walden, he wrote the lecture that he would later shape into the essay known as “Civil Disobedience”.

This last year has been for many of us a time of imposed seclusion in which we have chosen to read more, to spend more time in nature, and to think through our relationship with our government and reflect upon our thoughts and actions regarding race, equity, and equality. Could it be that COVID-19 in some ways has been our Walden?

If you go to Walden Pond today, you will not find the cabin there. Instead, you will find a pile of rocks (cairn) which was begun in improvisation in 1872 by the suffragist Mary Newbury Adams, a Thoreau fan. By then, any physical trace of Thoreau was long gone and there was nothing to signal the site’s significance. Mrs. Adams suggested that visitors to Walden bring a small stone for Thoreau’s monument, thus beginning the pile by laying a stone on the site of his hermitage. Word went out and the custom spread as, over the years, more pilgrims came. Some took a stone from the pond’s edge and placed it there, others took a stone from the pile to take home, and like nature itself, this monument for Thoreau became organic, and remains in perpetual flux.

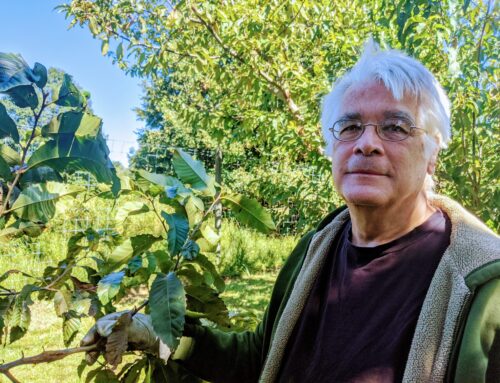

There are many different versions of Thoreau to commemorate: the environmentalist, the minimalist, the abolitionist, the ethnologist, and the anti-imperialist, who earned such followers as Tolstoy, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. I am so glad Tyler Arboretum has decided to commemorate him by placing a replica of his cabin there. It seems so fitting, and so needed by many of us.

This week will be no different when I go to Tyler; I will once again stop by to visit Thoreau’s studio, laboratory, observatory, and watchtower, and there I will place my own stone. Given this year, I know why Thoreau’s cabin is at Tyler. May you too find the answer to this most intriguing of questions. And when you visit, don’t forget your stone.