For some people, when they hear the term “spring”, their minds fill with bright, colorful images of flowers in bloom. For others, it’s frogs singing, the smell of mulch or fresh cut grass. Still, others think of resuming outdoor activities put on hold by winter weather, like picnics, grilling and going to baseball games. These clues all tell us that winter is over and spring has arrived again. But some of these signs are changing, showing us clear and measurable evidence of climate change in action.

For instance, many people from Washington, D.C. to Kyoto, Japan, and even right here at Tyler, eagerly await the appearance of cherry blossoms, but these flowers are opening sooner than they ever have. In Kyoto, Japan residents have been recording when the cherry blossoms are in full bloom each year. This year is the earliest date of the observed bloom (March 26) across the entire data set, going back to its first observation in 812 (yes, that’s year 812!).

Washington, D.C. is also seeing a change, with peak bloom dates for the cherry trees occurring earlier than it did in the past. Since 1921, peak bloom dates have shifted earlier by approximately five days (see EPA data). That might not sound like much time, but it represents a slow but steady movement to earlier and earlier flowers.

What about those spring signs that have nothing to do with flowers? For some people, the true start to spring is when Major League Baseball resumes and the teams begin their spring training. That date is determined by people, not by weather. We decide when we start to ‘play ball.’ So surely nothing about that could have changed, right?

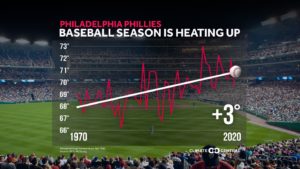

On April 1, our Philadelphia Phillies kicked off the 2021 season with a home opener against Atlanta. There was something different this year though, from what the Phillies experienced during their home opener against the Chicago Cubs in 1970 – warmer temperatures in the stadium. Since 1970, MLB cities have warmed an average of 2.1°F during baseball season. In Philadelphia, the temperature has risen 3.0°F. Fans sitting in the stands may be noticing the increasing temperature, frequency of heavy rain and extreme heat over the years. Being in warmer and more humid conditions may not be fun for sitting outside, but baseballs travel farther in this less dense air – meaning, more home runs!

Graphic from Climate Central can be downloaded here

Both of these examples are compelling evidence for the impact that climate change is already having on our lives. What do we mean when we say climate change, and how is that different from weather? Although climate and weather are related, they are not the same. Weather is the short-term state of the atmosphere, defined by location and time. We look at temperature, precipitation, wind speed, humidity levels and additional variables which can change very quickly, in a matter of minutes. As we record these weather data over a 30-year time period and create a record of these changes in a particular location, we can determine the long-term weather pattern, or climate. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has an excellent overview of how we get from weather observations to climate data, but here’s a quick and easy way to remember the difference – climate is what you expect, weather is what you get. In the graph for the Philadelphia Phillies, the red line represents the weather (temperature) record, and the white line shows the overall change in climate.

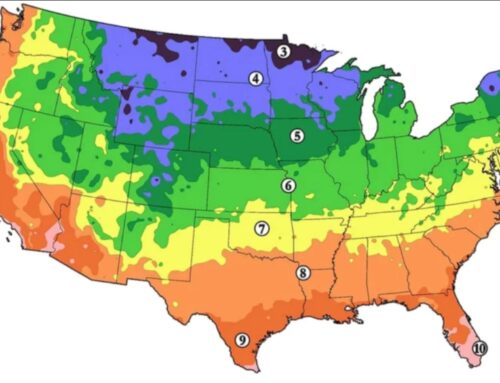

Earlier bloom times for flowering plants and warmer weather on opening day are just a few of the effects we’re already observing, but there are many, many more. The species we can grow in our gardens here in Philadelphia are changing as well. For instance, take the example of the southern live oak (Quercus virginiana). It’s an iconic species throughout the southern United States. It reaches about 80 feet tall, and can spread for 100 feet and is often seen draped with Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides). This stately tree is hardy only in zones 8 – 10, meaning that it isn’t cold tolerant enough to grow here in Southeastern PA. Our cold winter means that historically this area is zone 6 or 7.

We can say certainly that, at least historically, live oaks can’t survive long here – because Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania tried to grow them. Back in the 1950s they received a number of live oak acorns, which they grew on and planted out as part of their Michaux Quercetum project. Their goal was to establish a range of oak species on their Bloomfield Farm property, including the southern live oak, but every one of those saplings died — victims of our cold Pennsylvania winters.

That was 70 years ago. Flash forward to 2012, when Morris began to look at this species again. The average temperatures in our area had changed enough for another attempt to be made. Acorns were collected from live oaks found growing in the northernmost parts of their range, including the Richmond area, Williamsburg, Fort Munroe and Virginia Beach. For more information, you can refer to ‘The Quest for the Hardy Southern Live Oak’ by Michael S. Dosmann and Anthony S. Aiello. Morris Arboretum grew those acorns in their greenhouse complex and planted the resulting trees in their nursery on Bloomfield Farm in 2016. Their goal was to see if any were able to survive our cold winter weather.

Nearly five years has gone by and every one of them still grows. You can see them in this photo, taken March of 2021.

That doesn’t seem like a bad thing. Live oaks are beautiful trees, and who doesn’t love more trees? But the flip side to gaining the ability to grow some of our favorite southern species is losing the ability to grow other favorite plants that are less tolerant of heat, i.e. the sugar maple, Acer saccharum. As we explored in our article, ‘A Sticky Future for Maple Trees’ by Dr. Laura Guertin, sugar maples are declining in both health and syrup production in Southeastern PA, stressed by our warmer, wetter winters.

One question we will ask ourselves more and more as we observe species continuing to shift northwards and flowers starting to open earlier in the season, is what the impact will be on the birds, bees and other insect species who rely on those plants. Monarch butterflies are a great example. Their northern migration is tied to the bloom times of the flowers they need for nectar. If they arrive too late and find that those flowers have already bloomed, the monarchs might not make it. Migrating birds will encounter the same issue. If they arrive too late, and the berries they need are gone, they will have no food to fuel their southern flight. We don’t know exactly what impact the changing climate will have on the ecosystem at large. But we do know that it has already begun to see evidence of its effect.

Climate change will mean just that – change — for both our gardens and the seasonal cues we look for every year. Hotter summers and record–breaking storms add up to real alterations, both our weather and our climate. In fact, according to forestadaptation.org, by the year 3000 our weather here in the suburbs of Philadelphia might be much closer to zones 8 or 9; the weather in the modern–day Carolinas.

We’re not quite sure what our gardens, or our spring traditions, will look like in 100 years. We know they will be different, and in fact have already changed. Perhaps you’ve noticed this change yourself. You might have a magnolia that used to reliably bloom in April, that opens its buds now in March. Perhaps you’re having to break out the lawn mower earlier and earlier each season, to catch up to the onion grass. Maybe herbs that never over-wintered in your vegetable garden are appearing now year after year. Let us know! These observations give us clues to what the next few decades will hold, for our gardens, our weather, and the ecosystem as a whole.